The suburb of Saffron Park lay on the sunset side of London, as red and ragged as a cloud of sunset. It was built of a bright brick throughout; its sky-line was fantastic, and even its ground plan was wild. It had been the outburst of a speculative builder, faintly tinged with art, who called its architecture sometimes Elizabethan and sometimes Queen Anne, apparently under the impression that the two sovereigns were identical. It was described with some justice as an artistic colony, though it never in any definable way produced any art. But although its pretensions to be an intellectual centre were a little vague, its pretensions to be a pleasant place were quite indisputable. The stranger who looked for the first time at the quaint red houses could only think how very oddly shaped the people must be who could fit in to them. Nor when he met the people was he disappointed in this respect. The place was not only pleasant, but perfect, if once he could regard it not as a deception but rather as a dream. Even if the people were not “artists,” the whole was nevertheless artistic. That young man with the long, auburn hair and the impudent face—that young man was not really a poet; but surely he was a poem. That old gentleman with the wild, white beard and the wild, white hat—that venerable humbug was not really a philosopher; but at least he was the cause of philosophy in others. That scientific gentleman with the bald, egg-like head and the bare, bird-like neck had no real right to the airs of science that he assumed. He had not discovered anything new in biology; but what biological creature could he have discovered more singular than himself? Thus, and thus only, the whole place had properly to be regarded; it had to be considered not so much as a workshop for artists, but as a frail but finished work of art. A man who stepped into its social atmosphere felt as if he had stepped into a written comedy.

More especially this attractive unreality fell upon it about nightfall, when the extravagant roofs were dark against the afterglow and the whole insane village seemed as separate as a drifting cloud. This again was more strongly true of the many nights of local festivity, when the little gardens were often illuminated, and the big Chinese lanterns glowed in the dwarfish trees like some fierce and monstrous fruit. And this was strongest of all on one particular evening, still vaguely remembered in the locality, of which the auburn-haired poet was the hero. It was not by any means the only evening of which he was the hero. On many nights those passing by his little back garden might hear his high, didactic voice laying down the law to men and particularly to women. The attitude of women in such cases was indeed one of the paradoxes of the place. Most of the women were of the kind vaguely called emancipated, and professed some protest against male supremacy. Yet these new women would always pay to a man the extravagant compliment which no ordinary woman ever pays to him, that of listening while he is talking. And Mr. Lucian Gregory, the red-haired poet, was really (in some sense) a man worth listening to, even if one only laughed at the end of it. He put the old cant of the lawlessness of art and the art of lawlessness with a certain impudent freshness which gave at least a momentary pleasure. He was helped in some degree by the arresting oddity of his appearance, which he worked, as the phrase goes, for all it was worth. His dark red hair parted in the middle was literally like a woman’s, and curved into the slow curls of a virgin in a pre-Raphaelite picture. From within this almost saintly oval, however, his face projected suddenly broad and brutal, the chin carried forward with a look of cockney contempt. This combination at once tickled and terrified the nerves of a neurotic population. He seemed like a walking blasphemy, a blend of the angel and the ape.

This particular evening, if it is remembered for nothing else, will be remembered in that place for its strange sunset. It looked like the end of the world. All the heaven seemed covered with a quite vivid and palpable plumage; you could only say that the sky was full of feathers, and of feathers that almost brushed the face. Across the great part of the dome they were grey, with the strangest tints of violet and mauve and an unnatural pink or pale green; but towards the west the whole grew past description, transparent and passionate, and the last red-hot plumes of it covered up the sun like something too good to be seen. The whole was so close about the earth, as to express nothing but a violent secrecy. The very empyrean seemed to be a secret. It expressed that splendid smallness which is the soul of local patriotism. The very sky seemed small.

I say that there are some inhabitants who may remember the evening if only by that oppressive sky. There are others who may remember it because it marked the first appearance in the place of the second poet of Saffron Park. For a long time the red-haired revolutionary had reigned without a rival; it was upon the night of the sunset that his solitude suddenly ended. The new poet, who introduced himself by the name of Gabriel Syme was a very mild-looking mortal, with a fair, pointed beard and faint, yellow hair. But an impression grew that he was less meek than he looked. He signalised his entrance by differing with the established poet, Gregory, upon the whole nature of poetry. He said that he (Syme) was poet of law, a poet of order; nay, he said he was a poet of respectability. So all the Saffron Parkers looked at him as if he had that moment fallen out of that impossible sky.

In fact, Mr. Lucian Gregory, the anarchic poet, connected the two events.

“It may well be,” he said, in his sudden lyrical manner, “it may well be on such a night of clouds and cruel colours that there is brought forth upon the earth such a portent as a respectable poet. You say you are a poet of law; I say you are a contradiction in terms. I only wonder there were not comets and earthquakes on the night you appeared in this garden.”

The man with the meek blue eyes and the pale, pointed beard endured these thunders with a certain submissive solemnity. The third party of the group, Gregory’s sister Rosamond, who had her brother’s braids of red hair, but a kindlier face underneath them, laughed with such mixture of admiration and disapproval as she gave commonly to the family oracle.

Gregory resumed in high oratorical good humour.

“An artist is identical with an anarchist,” he cried. “You might transpose the words anywhere. An anarchist is an artist. The man who throws a bomb is an artist, because he prefers a great moment to everything. He sees how much more valuable is one burst of blazing light, one peal of perfect thunder, than the mere common bodies of a few shapeless policemen. An artist disregards all governments, abolishes all conventions. The poet delights in disorder only. If it were not so, the most poetical thing in the world would be the Underground Railway.”

“So it is,” said Mr. Syme.

“Nonsense!” said Gregory, who was very rational when anyone else attempted paradox. “Why do all the clerks and navvies in the railway trains look so sad and tired, so very sad and tired? I will tell you. It is because they know that the train is going right. It is because they know that whatever place they have taken a ticket for that place they will reach. It is because after they have passed Sloane Square they know that the next station must be Victoria, and nothing but Victoria. Oh, their wild rapture! oh, their eyes like stars and their souls again in Eden, if the next station were unaccountably Baker Street!”

“It is you who are unpoetical,” replied the poet Syme. “If what you say of clerks is true, they can only be as prosaic as your poetry. The rare, strange thing is to hit the mark; the gross, obvious thing is to miss it. We feel it is epical when man with one wild arrow strikes a distant bird. Is it not also epical when man with one wild engine strikes a distant station? Chaos is dull; because in chaos the train might indeed go anywhere, to Baker Street or to Bagdad. But man is a magician, and his whole magic is in this, that he does say Victoria, and lo! it is Victoria. No, take your books of mere poetry and prose; let me read a time table, with tears of pride. Take your Byron, who commemorates the defeats of man; give me Bradshaw, who commemorates his victories. Give me Bradshaw, I say!”

“Must you go?” inquired Gregory sarcastically.

“I tell you,” went on Syme with passion, “that every time a train comes in I feel that it has broken past batteries of besiegers, and that man has won a battle against chaos. You say contemptuously that when one has left Sloane Square one must come to Victoria. I say that one might do a thousand things instead, and that whenever I really come there I have the sense of hairbreadth escape. And when I hear the guard shout out the word ‘Victoria,’ it is not an unmeaning word. It is to me the cry of a herald announcing conquest. It is to me indeed ‘Victoria;’ it is the victory of Adam.”

Gregory wagged his heavy, red head with a slow and sad smile.

“And even then,” he said, “we poets always ask the question, ‘And what is Victoria now that you have got there?’ You think Victoria is like the New Jerusalem. We know that the New Jerusalem will only be like Victoria. Yes, the poet will be discontented even in the streets of heaven. The poet is always in revolt.”

“There again,” said Syme irritably, “what is there poetical about being in revolt? You might as well say that it is poetical to be sea-sick. Being sick is a revolt. Both being sick and being rebellious may be the wholesome thing on certain desperate occasions; but I’m hanged if I can see why they are poetical. Revolt in the abstract is—revolting. It’s mere vomiting.”

The girl winced for a flash at the unpleasant word, but Syme was too hot to heed her.

“It is things going right,” he cried, “that is poetical I Our digestions, for instance, going sacredly and silently right, that is the foundation of all poetry. Yes, the most poetical thing, more poetical than the flowers, more poetical than the stars—the most poetical thing in the world is not being sick.”

“Really,” said Gregory superciliously, “the examples you choose—”

“I beg your pardon,” said Syme grimly, “I forgot we had abolished all conventions.”

For the first time a red patch appeared on Gregory’s forehead.

“You don’t expect me,” he said, “to revolutionise society on this lawn?”

Syme looked straight into his eyes and smiled sweetly.

“No, I don’t,” he said; “but I suppose that if you were serious about your anarchism, that is exactly what you would do.”

Gregory’s big bull’s eyes blinked suddenly like those of an angry lion, and one could almost fancy that his red mane rose.

“Don’t you think, then,” he said in a dangerous voice, “that I am serious about my anarchism?”

“I beg your pardon?” said Syme.

“Am I not serious about my anarchism?” cried Gregory, with knotted fists.

“My dear fellow!” said Syme, and strolled away.

With surprise, but with a curious pleasure, he found Rosamond Gregory still in his company.

“Mr. Syme,” she said, “do the people who talk like you and my brother often mean what they say? Do you mean what you say now?”

Syme smiled.

“Do you?” he asked.

“What do you mean?” asked the girl, with grave eyes.

“My dear Miss Gregory,” said Syme gently, “there are many kinds of sincerity and insincerity. When you say ‘thank you’ for the salt, do you mean what you say? No. When you say ‘the world is round,’ do you mean what you say? No. It is true, but you don’t mean it. Now, sometimes a man like your brother really finds a thing he does mean. It may be only a half-truth, quarter-truth, tenth-truth; but then he says more than he means—from sheer force of meaning it.”

She was looking at him from under level brows; her face was grave and open, and there had fallen upon it the shadow of that unreasoning responsibility which is at the bottom of the most frivolous woman, the maternal watch which is as old as the world.

“Is he really an anarchist, then?” she asked.

“Only in that sense I speak of,” replied Syme; “or if you prefer it, in that nonsense.”

She drew her broad brows together and said abruptly:

“He wouldn’t really use—bombs or that sort of thing?”

Syme broke into a great laugh, that seemed too large for his slight and somewhat dandified figure.

“Good Lord, no!” he said, “that has to be done anonymously.”

And at that the corners of her own mouth broke into a smile, and she thought with a simultaneous pleasure of Gregory’s absurdity and of his safety.

Syme strolled with her to a seat in the corner of the garden, and continued to pour out his opinions. For he was a sincere man, and in spite of his superficial airs and graces, at root a humble one. And it is always the humble man who talks too much; the proud man watches himself too closely. He defended respectability with violence and exaggeration. He grew passionate in his praise of tidiness and propriety. All the time there was a smell of lilac all round him. Once he heard very faintly in some distant street a barrel-organ begin to play, and it seemed to him that his heroic words were moving to a tiny tune from under or beyond the world.

He stared and talked at the girl’s red hair and amused face for what seemed to be a few minutes; and then, feeling that the groups in such a place should mix, rose to his feet. To his astonishment, he discovered the whole garden empty. Everyone had gone long ago, and he went himself with a rather hurried apology. He left with a sense of champagne in his head, which he could not afterwards explain. In the wild events which were to follow this girl had no part at all; he never saw her again until all his tale was over. And yet, in some indescribable way, she kept recurring like a motive in music through all his mad adventures afterwards, and the glory of her strange hair ran like a red thread through those dark and ill-drawn tapestries of the night. For what followed was so improbable, that it might well have been a dream.

When Syme went out into the starlit street, he found it for the moment empty. Then he realised (in some odd way) that the silence was rather a living silence than a dead one. Directly outside the door stood a street lamp, whose gleam gilded the leaves of the tree that bent out over the fence behind him. About a foot from the lamp-post stood a figure almost as rigid and motionless as the lamp-post itself. The tall hat and long frock coat were black; the face, in an abrupt shadow, was almost as dark. Only a fringe of fiery hair against the light, and also something aggressive in the attitude, proclaimed that it was the poet Gregory. He had something of the look of a masked bravo waiting sword in hand for his foe.

He made a sort of doubtful salute, which Syme somewhat more formally returned.

“I was waiting for you,” said Gregory. “Might I have a moment’s conversation?”

“Certainly. About what?” asked Syme in a sort of weak wonder.

Gregory struck out with his stick at the lamp-post, and then at the tree. “About this and this,” he cried; “about order and anarchy. There is your precious order, that lean, iron lamp, ugly and barren; and there is anarchy, rich, living, reproducing itself—there is anarchy, splendid in green and gold.”

“All the same,” replied Syme patiently, “just at present you only see the tree by the light of the lamp. I wonder when you would ever see the lamp by the light of the tree.” Then after a pause he said, “But may I ask if you have been standing out here in the dark only to resume our little argument?”

“No,” cried out Gregory, in a voice that rang down the street, “I did not stand here to resume our argument, but to end it for ever.”

The silence fell again, and Syme, though he understood nothing, listened instinctively for something serious. Gregory began in a smooth voice and with a rather bewildering smile.

“Mr. Syme,” he said, “this evening you succeeded in doing something rather remarkable. You did something to me that no man born of woman has ever succeeded in doing before.”

“Indeed!”

“Now I remember,” resumed Gregory reflectively, “one other person succeeded in doing it. The captain of a penny steamer (if I remember correctly) at Southend. You have irritated me.”

“I am very sorry,” replied Syme with gravity.

“I am afraid my fury and your insult are too shocking to be wiped out even with an apology,” said Gregory very calmly. “No duel could wipe it out. If I struck you dead I could not wipe it out. There is only one way by which that insult can be erased, and that way I choose. I am going, at the possible sacrifice of my life and honour, to prove to you that you were wrong in what you said.”

“In what I said?”

“You said I was not serious about being an anarchist.”

“There are degrees of seriousness,” replied Syme. “I have never doubted that you were perfectly sincere in this sense, that you thought what you said well worth saying, that you thought a paradox might wake men up to a neglected truth.”

Gregory stared at him steadily and painfully.

“And in no other sense,” he asked, “you think me serious? You think me a flâneur who lets fall occasional truths. You do not think that in a deeper, a more deadly sense, I am serious.”

Syme struck his stick violently on the stones of the road.

“Serious!” he cried. “Good Lord! is this street serious? Are these damned Chinese lanterns serious? Is the whole caboodle serious? One comes here and talks a pack of bosh, and perhaps some sense as well, but I should think very little of a man who didn’t keep something in the background of his life that was more serious than all this talking—something more serious, whether it was religion or only drink.”

“Very well,” said Gregory, his face darkening, “you shall see something more serious than either drink or religion.”

Syme stood waiting with his usual air of mildness until Gregory again opened his lips.

“You spoke just now of having a religion. Is it really true that you have one?”

“Oh,” said Syme with a beaming smile, “we are all Catholics now.”

“Then may I ask you to swear by whatever gods or saints your religion involves that you will not reveal what I am now going to tell you to any son of Adam, and especially not to the police? Will you swear that! If you will take upon yourself this awful abnegations if you will consent to burden your soul with a vow that you should never make and a knowledge you should never dream about, I will promise you in return—”

“You will promise me in return?” inquired Syme, as the other paused.

“I will promise you a very entertaining evening.” Syme suddenly took off his hat.

“Your offer,” he said, “is far too idiotic to be declined. You say that a poet is always an anarchist. I disagree; but I hope at least that he is always a sportsman. Permit me, here and now, to swear as a Christian, and promise as a good comrade and a fellow-artist, that I will not report anything of this, whatever it is, to the police. And now, in the name of Colney Hatch, what is it?”

“I think,” said Gregory, with placid irrelevancy, “that we will call a cab.”

He gave two long whistles, and a hansom came rattling down the road. The two got into it in silence. Gregory gave through the trap the address of an obscure public-house on the Chiswick bank of the river. The cab whisked itself away again, and in it these two fantastics quitted their fantastic town.

| Copyright © | G. K. Chesterton, 1908 |

|---|---|

| By the same author | There are no more works at Badosa.com |

| Date of publication | November 2004 |

| Collection | Worldwide Classics |

| Permalink | https://badosa.com/n216-01 |

Creo que GK Chesterton es uno de los pensadores más completos de los últimos siglos y, por lejos, el más lúcido del siglo XX.

Sin duda, Chesterton es un ensayista y pensador inteligente, pero lo que hace que sus ensayos tengan ese atractivo especial son, ante todo, esas gemas brillantes que los enriquecen: me refiero a sus paradojas desopilantes.

En el siglo XX, existen ensayistas más demoledores y rigurosos (como Bertrand Russell o George Santayana) que Chesterton, básicamente porque no mezclaban poesía y filosofía en la argumentación de sus textos, lo cual los hace más rigurosos y científicos, pero menos divertidos que los del vecino de Beaconsfield.

Comoquiera que un ensayo debe ser inteligente y divertido, Chesterton sí podría ocupar el nº 1 como maestro en el ensayo genérico, pero no como el nº 1 en ensayo filosófico, que ocuparía seguramente Russell o Santayana, ya que Chesterton dio muestras de ser más artista que filósofo (su prolijidad, sus ganas de "pintar el pueblo todo de rojo", es la razón, como se opina en la biografía de Ward). De hecho, su catolicismo le hizo demasiado conservador con respecto al sexo (del que en sus ensayos no se habla, si no es a la manera de San Pablo), al valor social de la mujer (en casa cuidando hijos), a la ciencia (v.g. criticó a Einstein dando por supuesto que la relatividad era un despropósito, sin justificar sus argumentos por la vía científica, sólo con poesía y teologia apologéticas; también luchó por demoler los cimientos del darwinismo con poesía, lo cual es poco riguroso, filosóficamene hablando), al Arte (criticó el verso libre con vehemencia en sus ensayos, cuando, paradójicamente, siempre sintió un amor whitmaniano; despreciaba a Picasso y a la vanguardia; nunca los entendió, ni pretendió hacerlo: en este sentido, Santayana como esteta fue mucho más apreciativo y un crítico más racional y medido; véase su The Sense of Beauty, o The Life of Reason para ello).

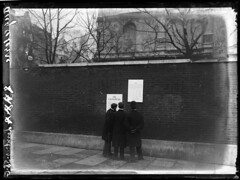

Besides sending your opinion about this work, you can add a photo (or more than one) to this page in three simple steps:

Find a photo related with this text at Flickr and, there, add the following tag: (machine tag)

To tag photos you must be a member of Flickr (don’t worry, the basic service is free).

Choose photos taken by yourself or from The Commons. You may need special privileges to tag photos if they are not your own. If the photo wasn’t taken by you and it is not from The Commons, please ask permission to the author or check that the license authorizes this use.

Once tagged, check that the new tag is publicly available (it may take some minutes) clicking the following link till your photo is shown: show photos

Even though Badosa.com does not display the identity of the person who added a photo, this action is not anonymous (tags are linked to the user who added them at Flickr). Badosa.com reserves the right to remove inappropriate photos. If you find a photo that does not really illustrate the work or whose license does not allow its use, let us know.

If you added a photo (for example, testing this service) that is not really related with this work, you can remove it deleting the machine tag at Flickr (step 1). Verify that the removal is already public (step 2) and then press the button at step 3 to update this page.

Badosa.com shows 10 photos per work maximum.